State of online dating

Find out how algorithms shape the apps and websites you use to find love.

Are dating apps a good part of the Internet? If you ask the people who make them, you get a resounding “Yes.” Match Group, the owner of Tinder and OkCupid, found in their 2018 survey that “singles met first dates on the internet more than through any other venue.” Those companies would like you to believe everyone is using dating apps, and they have the numbers to show it. I personally admire the creator of OkCupid, Christian Rudder, for his intense transparency and rigor in showing how dating apps work and how they’ve helped people meet each other.

But according to independent research, it’s hard to say how good dating apps really are. Despite so much online dating, Americans are feeling lonelier than ever. Some experts believe that’s because technology divides people. But other experts believe the difference in college education rates between men and women are really to blame for dating problems.

How men rated women on OkCupid, 2014

OkCupid publishes data about its users on its blog, OkTrends, where it measures how users' ratings relate to their race. Black women are consistently rated lower by all men, on average.

Trends in preferences on okcupid, 2009-2014

The ratings have persisted between 2009 and 2014. However, users have been reporting greater comfort with dating people different than them over time. Something about the app's design might play a role in the persistence these race-correlated ratings despite real changes in user's preferences.

trends in bias

When looking at dating app data specifically, Mr. Rudder once lamented that “on these sites black users, especially, there's a bias against them.” In contrast, there’s evidence that online dating is associated with greater rates of interracial marriage. There’s no consensus whether these apps made dating better or worse.

There’s one thing we can be certain about: Some people get much more from dating apps than others. As a millennial and game developer, I assure you that dating apps are a game, and there are winners and losers. But don’t take my word for it: read the online communities dedicated to online dating.

There, the people who get matches share strategies like what pickup lines to use, what times to start swiping, and even what species of pet you should pose with. The people who don’t get matches talk about past relationships, debate politics, or more often than not, blame women. The discourse around dating focuses on tips at the expense of what is really special about online dating: the algorithm.

Algorithms have changed over the course of dating app history. When the internet consisted of “bulletin board systems,” or digital notice boards of sorts, the algorithm for matching was essentially random. Whoever showed up on the website is who got matched with whom. Nowadays, there are still apps people use that work this way, like WeChat’s “Shake,” which matches two people as long as they’re shaking their phones at the same time.

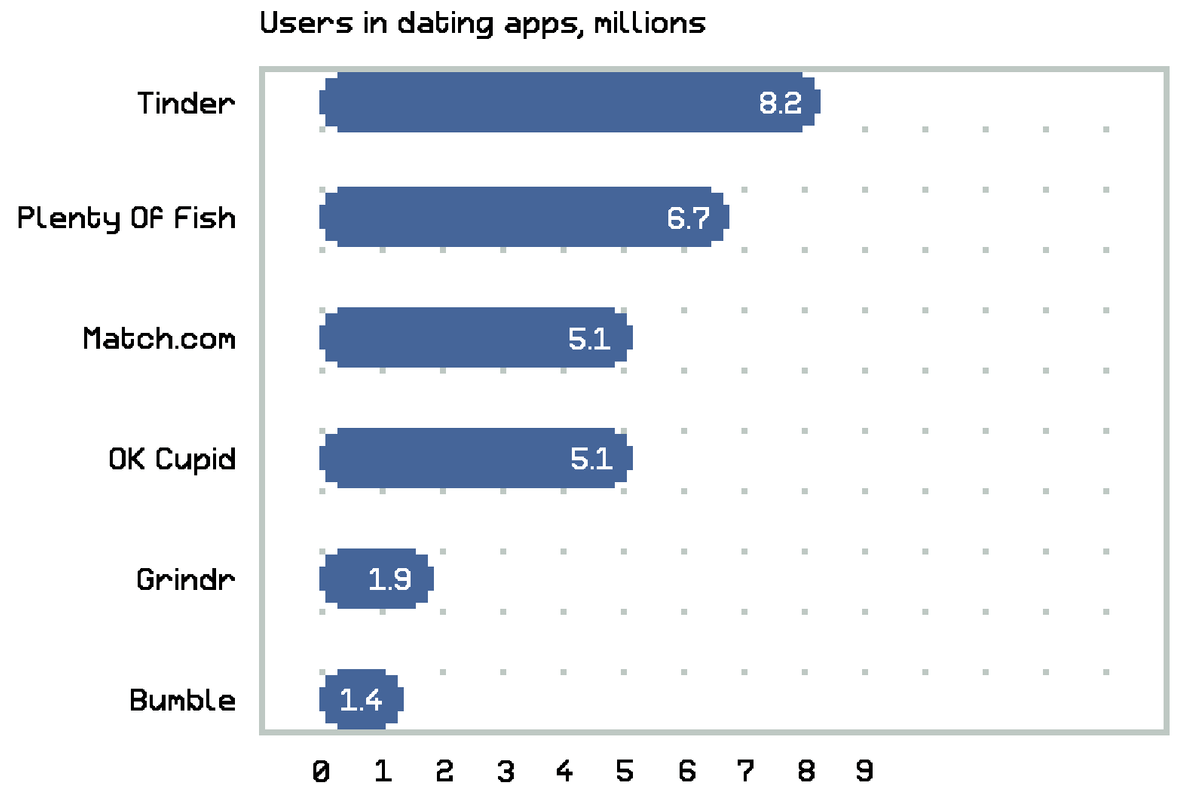

Audience size of dating apps, 2017

In December 2017, Statista, an industry data service, made these estimates of dating app audience sizes. This measures how many users have interacted with the specified app at least once in a given year. With 8.2 million users, Tinder is the largest dating app.

History

Later, dating apps matched people with some “sober arithmetic,” as the creator of OkCupid put it. The idea was that people who matched in terms of answers to personality questions, their appearance, their location, or other aspects of their daily lives would also be a good match romantically. This algorithm is a form of counting, where every matching aspect between two people gives the match a point, and every disagreement takes a point away. The best matches are the ones with the highest scores—a good match in the sense of having a lot in common, essentially.

Nowadays, apps use collaborative filtering, a sophisticated algorithm famously used to make movie recommendations based on previous movies you’ve watched. Collaborative filtering tries to find groups of people with shared preferences, whatever they are, and then makes recommendations to the individual based on the preferences of the group. Instead of needing to come up with all the different things that people could have in common (their age, their hometown, their taste in music, their feelings on smoking, to name a few from OkCupid), the algorithm works no matter the reason people prefer one person over another.

The most important part of the state of online dating is that collaborative filtering is so effective it’s used by almost all apps. Users of dating apps make “yes” or “no” decisions on other users, one-by-one, and that data is counted to figure out whose preferences that user most resembles. Then, data from the older user is borrowed to make recommendations for the newer user: that’s how the next profile to show is determined. While many legacy dating applications let you browse, most people prefer being given a single profile to look at and making a yes/no decision. Apps have arrived on collaborative filtering both because it’s effective in terms of matching and also because its user interface design is preferred over browsing.

There are side-effects to collaborative filtering: users with uncommon preferences are poorly served by the algorithm. So app makers have made niche apps, each catering to a group of user, to make collaborative filtering more effective. There are dozens of special interest dating apps, like Amo Latina for Latino users, JDate for Jewish users, and Grinder for LGBT users. Most of these apps are owned by the same company (Match Group, a subsidiary of IAC). They’re not really different apps: they work the same, and even have the same interface.

But for a variety of reasons, they may attract users who have bad luck with collaborative filtering in apps with larger userbases like Tinder. A large userbase puts money in the company’s bank account. But a large userbase also makes uncommon preferences seem more uncommon and common preferences seem even more common.

There’s a tension between the effectiveness of collaborative filtering and a tech company’s objective to have as many users as possible. The result is many apps, owned by the same people, that divide users into religious, ethnic, sexual orientation, and geographic groups. That is the state of online dating today

© 2019 Hidden Switch